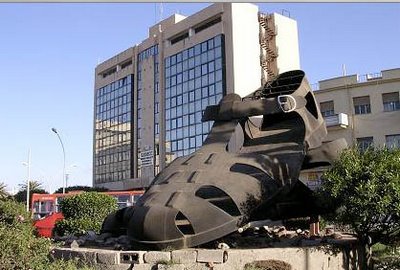

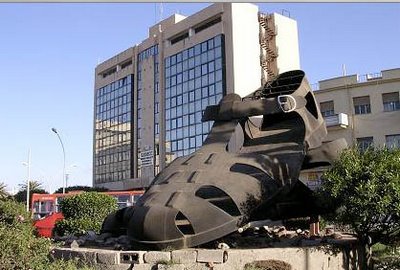

Occasionally, an everyday object with no special significance starts to loom large and meaningful in a different culture, in a faraway part of the world – as if in some parallel universe. Consider plastic sandals – a kind you pick up in 99c stores all around America. This unlikely object stands as a monument on a city square in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. The small East-African country split from Ethiopia after the long civil war in 1993, yet the struggle for independence continued well into the late 90s.

Occasionally, an everyday object with no special significance starts to loom large and meaningful in a different culture, in a faraway part of the world – as if in some parallel universe. Consider plastic sandals – a kind you pick up in 99c stores all around America. This unlikely object stands as a monument on a city square in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. The small East-African country split from Ethiopia after the long civil war in 1993, yet the struggle for independence continued well into the late 90s.

“It’s what all our fighters wore,” the New York Times quoted Eritrea’s ambassador to the US, who had a pair of sandals himself. “ We didn’t have uniforms. That was our uniform, and it became a symbol of our independence.” Machines for making sandals (“shida”) were set up near the front. Whenever a strap of a shida broke, it could be quickly fixed with a small flame by melting it back together.

This Oldenburg-like monument reminds us about relativity of values we attach to objects of our daily use. Is there a giant toothpaste memorial out there, somewhere?

J. Peterman Catalogue looks different from the bundle of similar offerings that arrive weekly in the mail. It is white; instead of assertive photos of male and female models, there are delicate watercolor renderings of clothes and merchandise. None of it appears too distinctive or special, until you start to look and read closer.

J. Peterman Catalogue looks different from the bundle of similar offerings that arrive weekly in the mail. It is white; instead of assertive photos of male and female models, there are delicate watercolor renderings of clothes and merchandise. None of it appears too distinctive or special, until you start to look and read closer.

A shirt on sale is a copy of one worn by Thomas Jefferson, a striped t-shirt was spotted on Picasso in St. Tropez, and a long-billed cap once belonged to Hemingway. “He probably bought his in a gas station on

the road to Ketchum, next to the cash register, among the beef jerky wrapped in cellophane,” – intones the catalogue.

How does it feel to wear a copy of Hemingway’s cap? Do you feel empowered? amused? – or does it make a cute conversation topic? (I am tempted to order one and try it out.)

These references to cultural history clearly endow J. Peterman merchandise with a certain aura. In a highly saturated fashion market, these humble, not-inexpensive caps and shirts are able to stand their own ground. Fashion industry is always the first to tap into consumers’ hidden cultural desires. I could see product and furniture design following suit. Could offerings like John Lennon’s bed be far behind?

In the exhibition of Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, his images were interspersed amongst a peculiar selection of Japanese antiques. I was immediately attracted to the beautiful wooden miniature pagoda in the museum vitrine.

In the exhibition of Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, his images were interspersed amongst a peculiar selection of Japanese antiques. I was immediately attracted to the beautiful wooden miniature pagoda in the museum vitrine.

After civil disturbances in the 8th Century Japan, a new empress commissioned the production of these miniature pagodas for the repose of the souls of the war dead. ”Over a period of six years,” – writes Sugimoto, – “one million miniature pagodas were made and distributed to ten major temples (each receiving 100 thousand). Of the complete set, 45 thousand are estimated to survive to the present; the other 955 thousand were burned, discarded, or destroyed, disappearing in the intervening 1200 years of history”.

It is perhaps not so surprising that this impressive (even by today’s standards) mass production did not create a functional utilitarian item. Amidst poverty and war, instead of making a million chairs or bowls, the craftsmen concentrated their superhuman effort on producing miniature buildings! Today many would call them tchotchkes, back then they were considered indispensable for religious fulfillment and emotional consolation.

Could this first mass produced object be considered a paradigm of design? Or is it just a curious footnote to the debate about functional vs superfluous?