Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Need and Want

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

A Real Mendini

I got acquainted with Alessandro Mendini years before I actually met him. In the early 1980s, the Italian architect was at the helm of trendy and sophisticated Domus magazine, which in the world of publications stood out much like Apple stands in the computer industry today. Mendini’s perfect Milanese face looked straight on from the front page of every issue, where he interviewed his famous subjects. Those peculiar enigmatic interviews felt even more alluring because of my sketchy understanding of both Italian and English.

Domus Academy, where I came to Milan to study, was not directly linked to the magazine, yet Mendini’s reputation loomed larger than life over the entire school. Soon I met the man himself, who turned out to be only five-foot-four, but had an irresistible charisma. I learned also that many in Milan were unsure about his work: his message was too complex, too personal, and not too optimistic. Who else would dare to title his own monograph The Unhappy Design?

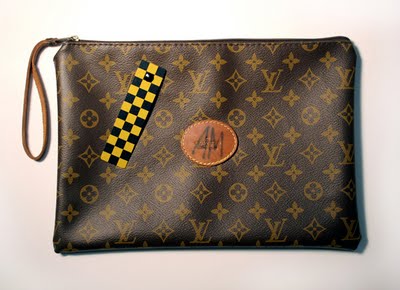

A good example of Mendini’s attitudes was a one-time performance, sometime in 1984, of which I kept an unusual souvenir: a fake Louis Vuitton purse. The counterfeits’ market was flourishing in Milan twenty-five years ago, as it probably continues to this day. The business was conducted on the street, mostly by vendors from Africa, known as “the Senegalese”. For the event, the architect had invited several of the men into an art gallery, along with their illegitimate wares. There was music and vine. Guests could buy a counterfeit bag, quite cheaply, and Mendini would then validate their purchase by attaching a new checkerboard tag and placing his initials over the old label. A fake Vuitton would become an original Mendini.

Many of design preoccupations of the time had found reflection in this simple gesture of the architect: the theme of banal object and originality, the politics of design, the redeeming quality of decoration. Above all, it had a fleeting lightness of a game. Soon the event was forgotten; I do not know how many redesigned bags, if any, remain today.

Around 1985, Alessandro Mendini joined forces with his architect-brother, Francesco, starting a second, “happy” phase of his career, which ultimately brought him much commercial success. By stroke of good fortune, I landed my first job after graduation in Mendini Brothers’ new architectural studio. Their first and only project was an unusual house on the lake Orta, entrusted to them by Alessandro’s old-time friend Alberto Alessi. Mendini’s concept was to extend his ideas of collaborative design to the scale of a villa. Different parts, designed by the likes of Michael Graves, Robert Venturi, Sottsass, even Frank Gehry, were to be merged into one coherent, decorative composition.

On my first day at work, Alessandro said with his characteristic smile: “Let’s play this game together.” Compared to my experience at American architectural offices, his work process did resemble playing. The architect would through around some outlandish ideas, which somehow would make a perfect answer to a problem at hand. Once, after we struggled in vain to line up the parapets of two joined roofs, he finally offered: “Let us just build the roofs first; then we’ll go up there, and figure it out.” Unfortunately, I did not have a chance to climb that roof. My calling soon brought me back to New York. Alessandro Mendini moved on to become a creative director at Swatch, and the brothers had built a host of Swatch stores around the world. We even managed to collaborate again – but that’s another story.